Table of Contents

Overview

In The Ladies Scared by a Mouse by Auguste Serrure (1825–1903), a small commotion becomes theatre. Two ladies recoil on a sofa while a gentleman kneels to peer beneath it. A gilded mirror, carved furniture, and patterned upholstery frame the moment; a dropped fan rests on the floor. Panic softens into laughter as elegance meets a trivial intruder.

This work belongs to Genre Painting / Rococo Revival in the 19th century, restaging eighteenth-century manners with academic finish. Rather than history or allegory, it records behavior and reaction. Serrure concentrates on gesture, costume, and interior craft, arranging clear sightlines so the viewer reads the narrative instantly, without captions or extraneous symbolism.

The mouse is the catalyst; the subject is character — poise, vanity, affection, and the way fear flips into amusement. By catching the pause before resolution, the painting suggests that refinement remains human and forgiving. The scene endures as a warm, precise comedy of manners, made memorable by craft, light, and timing.

A Small Panic in Silk

Laughter and elegance collide in this delightful scene by Belgian genre painter Auguste Serrure, who captured with wit and flair the theatrical spirit of upper-class interiors. Painted in the late 19th century, The Ladies Scared by a Mouse invites us not to tragedy or grandeur—but to the comedy of life’s smallest surprises.

In a room rich with Rococo embellishment, gold filigree, velvet, and lace, Serrure stages a scene as dramatic as any play—yet sparked by something as humble as a mouse.

The Ladies Scared by a Mouse: Comedy in Gold Trim

A gentleman in powdered wig and pink satin kneels on the floor, cane in one hand, the other stretched forward as he peers beneath the lavish furniture. His back is arched, and his body tense—not in pursuit of glory, but a tiny intruder.

Above him, two finely dressed women react in contrasting styles. One woman, dressed in soft cream with pink ribbons, has leapt onto the elegant couch, her posture alert, gaze locked on the floor. Beside her, a woman in black lounges with amused grace, her smile calm and her hand pointing helpfully toward the source of the commotion.

A fan lies forgotten on the floor—a casualty of the sudden flurry. Gold trim and floral patterns glimmer under the warm light, while ornate walls and heavy vases frame the drama with playful irony.

The Uninvited Guest

At first glance, the painting is pure humor—a slapstick ballet of manners interrupted. But Serrure’s genius lies in how he uses this light-hearted moment to offer a subtle commentary on the fragility of appearances.

In a world of luxury and etiquette, it takes only the scurry of a mouse to unravel the illusion of control. Fear becomes a great equalizer, cutting through decorum with surprising ease.

And yet, rather than mock, the painting celebrates. There’s affection in how Serrure renders each figure—especially the gentleman, whose exaggerated effort feels almost heroic in its own ridiculous way.

The Gallant and the Mouse

Serrure’s brushwork is detailed and refined, his color choices warm and theatrical. The stage-like composition, filled with flourishes and deep perspective, adds a sense of performance—as if we, too, are part of the audience.

The women’s dresses catch the light just so. The polish of the floor, the curl of the gentleman’s shoe, the dropped fan—each detail draws us further in, reminding us that even in gilded rooms, life is never without its surprises.

In the end, it’s not the mouse that matters—but the joy of watching what it brings out in us.

About the Artist

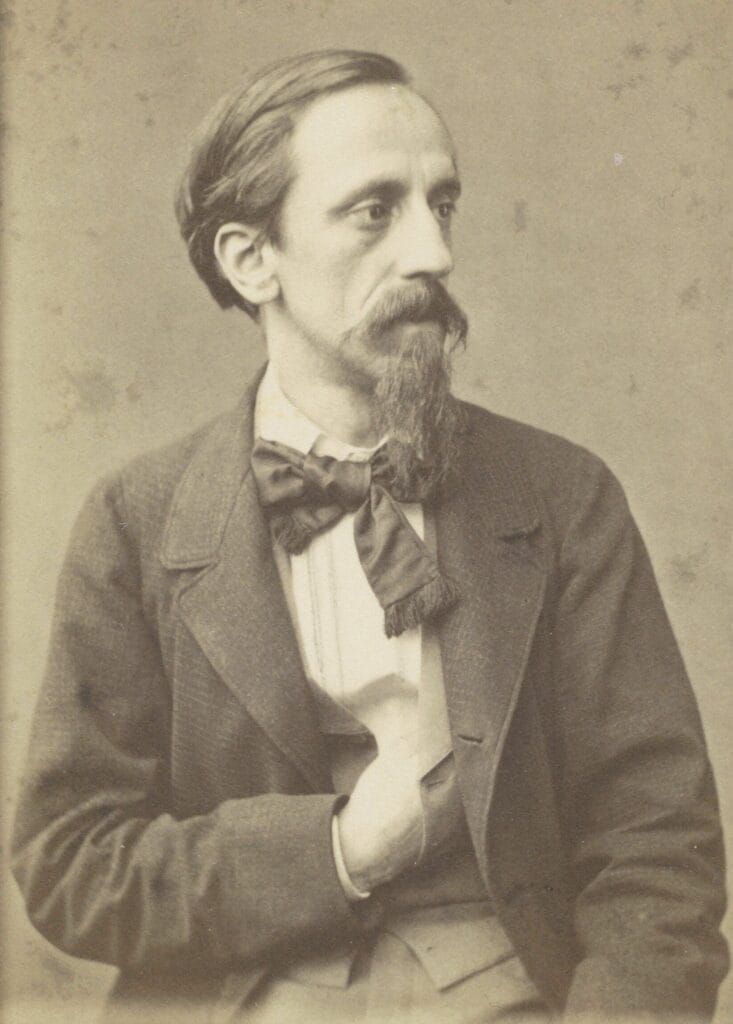

Auguste Serrure (1825–1903) was a Belgian painter celebrated for his genre scenes infused with Rococo charm and narrative vitality. Trained in Antwerp, he belonged to a circle of 19th-century artists who revived the elegance of 18th-century interiors while applying the technical precision of academic realism.

Serrure’s paintings often featured aristocratic subjects — gallant lovers, mischievous servants, and flirtatious encounters — all rendered with luminous color and impeccable detail. His works, including The Proposal, The Flirtation, and The Ladies Scared by a Mouse, reveal his gift for transforming small moments into stories filled with humor and human warmth.

While rooted in nostalgia, Serrure’s art also celebrates the enduring human spirit: lively, imperfect, and endlessly expressive.

The Story

A stately room glows with gilt mirrors, marble columns, and embroidered upholstery. Two women occupy the sofa — one in a pale cream gown trimmed with lace, the other in elegant black velvet. Both lean forward, alarmed yet amused, as a man in rose-colored silk drops to his knees in pursuit of a mouse.

The fan on the floor hints at the commotion — perhaps dropped during a sudden shriek. The women’s postures — one standing on the sofa, the other peering over the armrest — capture a moment suspended between fear and laughter.

The gentleman’s exaggerated gallantry, complete with wig, stockings, and cane, turns the incident into a miniature comedy. Serrure delights in the contrast: high fashion meets low chaos, elegance meets absurdity.

Artistic Context

In the late 19th century, European painters looked back to the Rococo period for inspiration. Artists such as Auguste Serrure, Jules Girardet, and Vittorio Reggianini reimagined the grace and humor of 18th-century France, reviving powdered wigs, silken gowns, and intimate interiors.

Serrure’s work, however, stands apart for its theatrical spontaneity. He paints not static poses but living gestures — startled, amused, and expressive. His style bridges Rococo’s decorative lightness and the disciplined realism of the academic era.

In The Ladies Scared by a Mouse, he blends both worlds: the opulence of Versailles and the laughter of everyday life.

Composition and Subject Matters

Serrure constructs the scene with exquisite balance. The sofa and mirror anchor the composition vertically, while the diagonal motion — from the lady’s lifted hem to the man’s bent figure — energizes the space. The fan, fallen at the lower left, adds a witty final touch of motion and imbalance.

The interplay of fabrics — ivory satin, black velvet, and rose silk — showcases Serrure’s mastery of texture and light. Reflections glint in the mirror and vase, while golden highlights trace every carved flourish.

Despite the comedy, the artist maintains harmony: every curve and color supports the rhythm of movement. The entire scene feels choreographed, like a dance of surprise.

Style and Technique

Serrure’s technique combines the smooth precision of the academic school with the coloristic flair of Rococo. His brushwork is controlled and fine, but light plays freely across surfaces, bringing warmth to marble, sheen to satin, and softness to skin.

His palette is a harmony of golds, creams, blush pinks, and deep blacks, balanced by touches of green and vermilion. The contrast between the women’s airy attire and the man’s heavier tones reinforces the comedic tension.

Every inch of the painting glows — not from theatrical lighting but from Serrure’s ability to turn luxury into atmosphere. His attention to detail never overwhelms; it delights.

Symbolism and Meaning

Beneath the laughter lies a gentle social satire.

- The mouse, though unseen, symbolizes the unpredictable — a reminder that even in refined surroundings, life resists control.

- The women’s reaction mocks polite hysteria, transforming fear into fashionable display.

- The man’s exaggerated chivalry lampoons the rituals of courtly behavior, suggesting that gallantry can be both noble and absurd.

Serrure invites viewers to smile — not at cruelty, but at recognition. Every human circle, from palace to parlor, shares the same blend of vanity and vulnerability.

The Ladies Scared by a Mouse

A rustle, a shriek,

a flutter of lace,

the calm of a salon undone.

He kneels for valor,

they rise for grace —

and laughter hides what fear has spun.