Table of Contents

Marcelle Roulin: The Face of a Pensioner

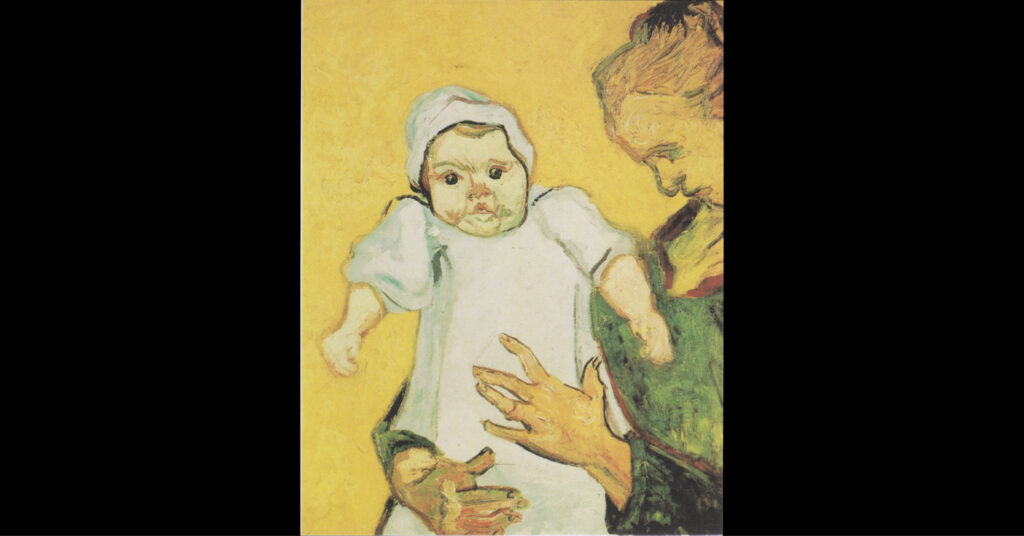

Van Gogh painted many forgettable faces. This baby is certainly not one of them.

Madame Roulin and Her Baby is meant to be tender. Maternal. Quiet. Intimate. Instead, it turns into a visual inconsistency: a three-month-old infant who seems to carry the burden of an old soul.

Painted in 1888 during Van Gogh’s vibrant period, the work feels like a strange detour from the muddy, earthy tones and humble subjects of his earliest Dutch paintings. While Vincent was pioneering a new language of color, baby Marcelle is rendered with such heavy impasto that her face takes on a lumpy, weathered texture, closer to a rustic vegetable than a porcelain child.

Between the electric yellow background and the mother’s oversized, slightly disembodied hands, the composition challenges nearly every traditional expectation of a precious portrait.

This painting has lived for more than a century inside major museum walls, mostly protected by the Van Gogh halo. Remove the halo, and you are left with something far stranger.

Quick Facts

Artwork Title: Madame Roulin and Her Baby

Artist: Vincent van Gogh

Year: 1888

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 25 × 20 in

Current Location: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Collection Type: Museum collection

Market Context & Provenance

Where This Painting Sits in the Van Gogh Market

Madame Roulin and Her Baby belongs to Van Gogh’s Arles portrait cycle, one of the most scrutinized and financially important bodies of work in nineteenth-century art. Paintings from this phase are treated as core Van Gogh material, not peripheral experiments, even when individual examples provoke discomfort.

Within this context, the painting is not considered a curiosity. It is considered a real Van Gogh. That distinction matters.

Provenance and Institutional Weight

The painting moved early from Van Gogh’s circle into private hands before eventually entering the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Museum acquisition at this level functions as a permanent validation mechanism. It anchors the work inside both scholarly and market ecosystems, regardless of aesthetic controversy.

Institutional provenance does not make a painting beautiful. It makes it permanent.

Comparable Works and Auction Presence

Comparable Van Gogh portraits from the Arles period have appeared repeatedly at major auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s. These sales establish the financial ceiling for Van Gogh’s figurative production from the late 1880s.

Within this tier of the market, decorative appeal is not the primary driver.

Tension is.

Portraits described as awkward, unresolved, or difficult routinely circulate at the highest levels because they remain embedded inside Van Gogh’s most studied and traded period.

Ugly does not mean marginal.

Why This Particular Painting Still Carries Weight

The discomfort of the baby’s face, the aggressive yellow background, and the heavy impasto are not side effects. They are the substance.

In the current luxury collecting climate, works that feel strange, abrasive, or visually uncomfortable are often read as more authentic than polite or decorative pictures. They signal proximity to the artist’s inner state rather than surface charm.

Pretty Van Gogh paintings are familiar.

Disturbing Van Gogh paintings feel closer.

Collectors are not competing for pleasantness.

They are competing for intensity, psychological charge, and historical friction.

This painting offers all three.

Its market strength does not exist in spite of its ugliness.

It exists because of it.

Aesthetic Breakdown

The baby’s face is a visual disaster. The head is too large. The cheeks bulge outward. The skin reads thick and waxy rather than soft. Instead of delicate infant flesh, we get something closer to kneaded dough. The eyes sit wide and heavy, giving the face a permanently exhausted expression. It feels less like a living child and more like a poorly stored museum replica.

Structural Problems

Structurally, the anatomy never locks in. The skull shape is vague. The neck barely connects. The shoulders dissolve into clothing. Modeling relies on heavy outlines instead of gradual tonal build-up. The hands suffer most. Fingers merge into blunt shapes. Knuckles are implied, not constructed. Perspective is shallow and unstable. The figure floats rather than inhabits space.

What People Have Said

Before the world decided Van Gogh was a visionary, many of his contemporaries experienced his work as a series of strange technical gambles that did not always land. While this portrait was meant to capture domestic calm inside the Roulin household, early viewers were often struck by how Vincent’s idea of infancy looked closer to seniority.

Thirty Years in the Post Office

The most persistent observation about baby Marcelle is that she appears ready to retire. Viewers and critics have long remarked on the infant’s dark, heavy eyes and the thick, shadowed texture of her face, which give her the look of a weary laborer rather than a newborn. Since Joseph Roulin was a postal worker, the unintended joke is hard to miss: Van Gogh seems to have painted the three-month-old with the same rugged intensity he used for the adults in the family.

The Mustard Pot Massacre

Accounts from Van Gogh’s time in Arles describe Paul Gauguin as openly skeptical of Vincent’s color excesses. Gauguin reportedly joked that Vincent was not painting so much as “playing with the mustard pot,” a jab aimed at his aggressive use of yellow. The blazing background behind Madame Roulin fits this description perfectly, vibrating so loudly that it threatens to overpower everything in front of it.

The Ghost Hands

Commentators have also fixated on the composition. Because Madame Roulin is largely cropped from view, the baby appears to be supported by two enormous, orange-toned hands floating in space. The effect has been jokingly compared to an ‘invisible mother,’ as if the child were being hoisted by a pair of ghostly gardener’s gloves rather than an actual human figure.

THE UGLY BABY

Van Gogh wanted tenderness. He delivered discomfort.

Madame Roulin and Her Baby survives on the artist’s reputation, not on visual success.

It is famous.

It is important.

It is also ugly.

All three are true.

Most historians agree the awkwardness was not intentional, and that Van Gogh simply struggled with painting children. That explanation is convenient.

But with this painting, it is hard not to wonder.

Van Gogh was not a gentle observer of the world. He was volatile, obsessive, and deeply unstable. He distorted reality everywhere else. Why assume he suddenly sought softness here?

Perhaps he did not fail to capture innocence.

Perhaps he did not want innocence.

We will never know.

And that uncertainty may be the most honest thing about this strange, unforgettable baby.

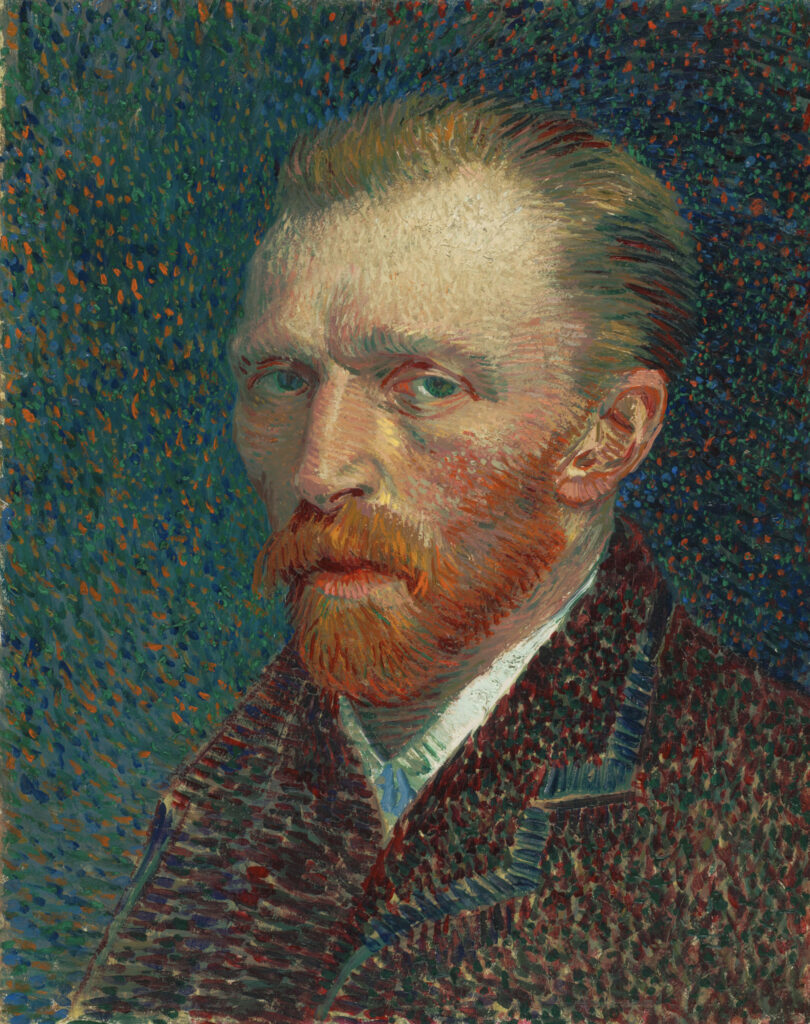

About the Artist

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter whose brief career produced more than 800 oil paintings and over 1,000 works on paper. Working largely outside academic systems, he developed a highly personal language of color, impasto, and line that influenced modern art profoundly. During his lifetime he sold almost nothing. Today, his work anchors museum collections worldwide and occupies a central position in the global art market.