Table of Contents

EDITORIAL

Inside Klimt’s Golden Spell

Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–1908)

There are paintings that you admire, and paintings you live inside.

Klimt’s The Kiss is the second kind. It appears simple, two lovers, wrapped in gold, held in a perfect moment. But looking longer, the painting begins to resist you. The bodies stop behaving like bodies. The space stops behaving like space. The scene becomes less like a painting and more like a sealed chamber.

Even the kiss itself is strange. It does not land the way we expect. It hovers. It pauses. It keeps its tension alive, as though Klimt refused to let the moment complete itself. And beneath them, the flowers end abruptly. The lovers kneel at the edge, where beauty has no future.

Everything in this scene is gold, yet nothing feels metallic. The world disappears, and the desire becomes ritual.

The air around them feels sacred, as if the painting has stopped time and locked the door. There is no before, no after, only this.

And somehow we are pulled into it. Not as observers, but as witnesses. Klimt does not paint a kiss to be watched. He paints a moment that asks to be believed.

Image Note

The artwork images in this issue are based on a high-quality public domain reproduction of Klimt’s The Kiss. For clarity, some views are cropped and zoomed to highlight specific details discussed in each section. Minor optimization may be applied to support legibility at screen and puzzle scale, without altering the painting’s content or meaning.

Interactive Detail Map

Tap the highlighted points on the painting to reveal hidden symbols, micro-details, and meaning.

#1 The Man

Klimt paints the man not as a romantic hero, but as a force. He enters the scene like a figure made of will, pattern, and intent, pressing forward into the woman’s space with a certainty that feels ceremonial, even overwhelming. His face is partly hidden; his body is almost fully overtaken by the hypnotic design. He is not defined by likeness. He is defined by role.

One persistent reading treats him as Klimt’s presence in disguise. Not a literal self-portrait, but an authorial stand‑in: the maker, the one who encloses the world in gold, the one who decides how intimacy appears within the frame. This is ‘Klimt’s position’ more than ‘Klimt’s face.’

His green crown is not social. It suggests nature and ritual, a mythic or pagan authority rather than modern Viennese realism. The robe reinforces this symbolic masculinity: hard rectangles, dark blocks, repetition, and structure. It behaves less like fabric and more like designed armor.

And then there is the reaction he provokes: the woman’s extreme tilt, the hinge-like neck. The kiss becomes not only affection but an event with gravity. Whether we read it as devotion or possession, the man is the initiating principle: enclosing, blessing, claiming, or offering himself into the union.

#2 The Woman

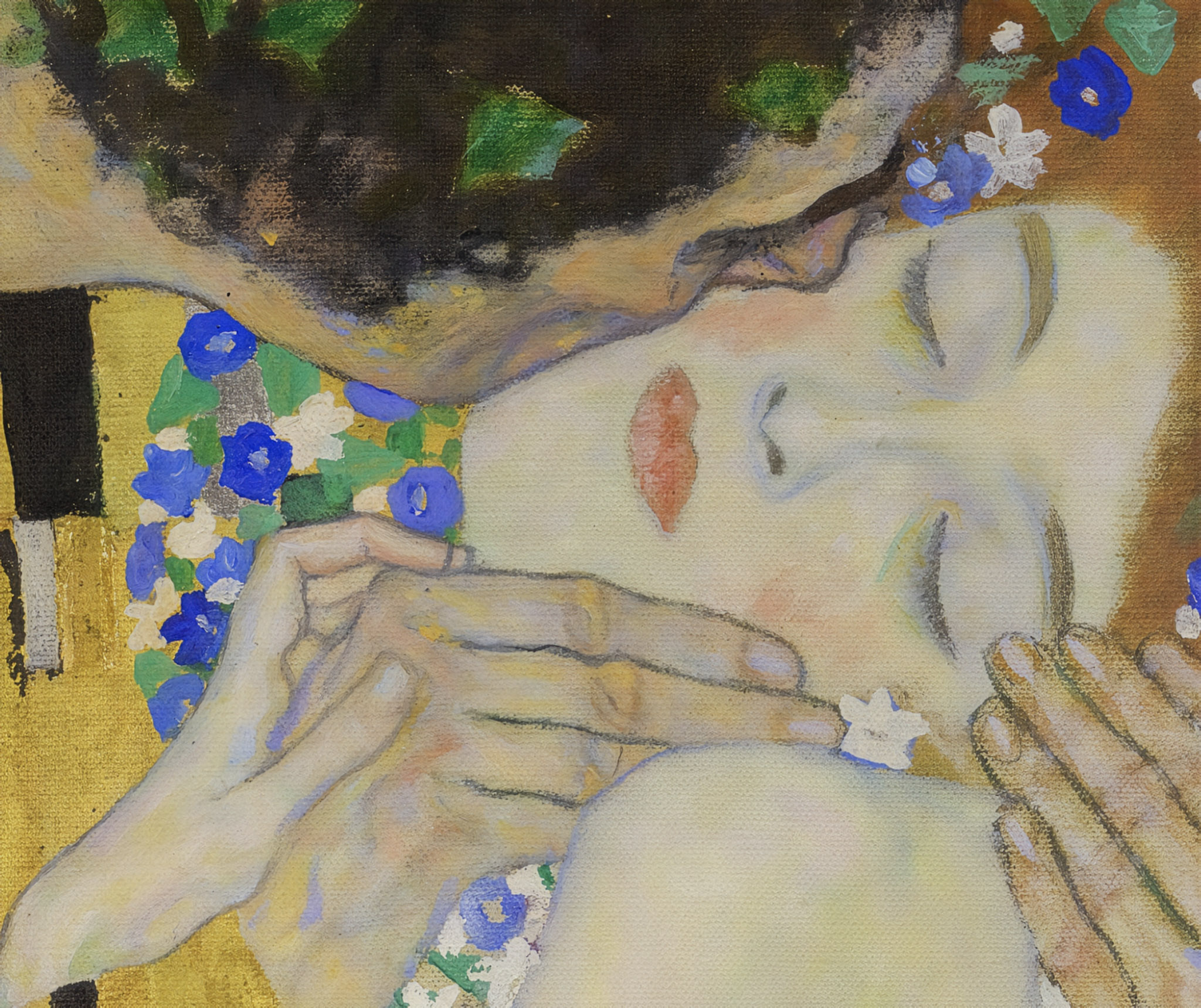

If the man is painted as a force, the woman is painted as a response. Klimt makes her the emotional instrument of the painting. Almost everything we feel in the scene is carried by her: closed eyes, softened mouth, hands that neither resist nor fight, and feet that register fragility.

The woman is often associated with Emilie Flöge, Klimt’s close companion. The identification persists because it ‘fits’ the emotional biography around Klimt, but it should be treated as tradition rather than proof. In the end, the painting asks us not to solve her identity, but to accept her as a type: the adored, the mythic, the eternal feminine made human.

Her crown of flowers aligns her with nature, innocence, and a kind of bridal sanctity. Her robe speaks a different language from his: circles, blossoms, organic repetition. Where his patterns declare structure and command, hers declare permeability and bloom.

Her reaction is distributed across her entire body. The extreme neck tilt suggests surrender and vulnerability at once. Her feet and curled toes grip the flower patch like a small truth the body cannot hide: nervousness, sensation, precariousness. Her hands and fingers may be the most decisive evidence of acceptance. They do not push away. They ‘sign’ the moment quietly, as if admitting, consenting, yielding. Klimt does not make this scene equal in action; he makes it equal in meaning.

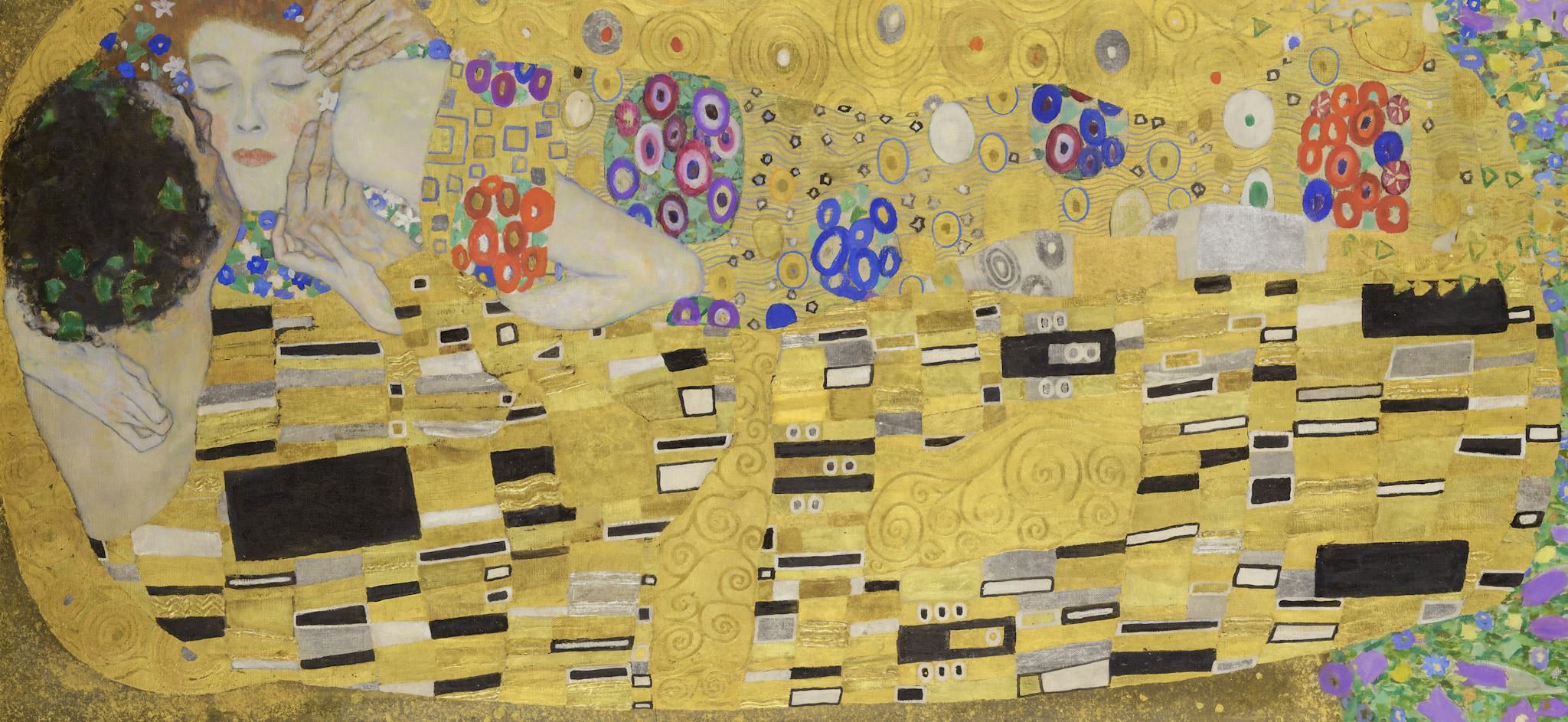

#3 The Aureole

The aureole in The Kiss is not just a golden object. It is a cocoon: a shared mantle that replaces ordinary space and turns the embrace into a sealed atmosphere. Klimt does not place the couple in a world; he wraps them inside one.

This cocoon can be read as protection, sanctity, and shelter. Yet it also introduces a powerful nuance: it seems to serve the woman most. It extends toward her side, gathers beneath her, and visually holds her feet at the precipice. It behaves like an offering.

A persuasive reading is that the cocoon feels like the man’s extension, sacrificed willingly for her safety. A portion remains in his robe as if the gold has migrated from him into a shared casing that catches her. This transforms the enclosure into support.

Common interpretations align the aureole with icon traditions. Gold fields in sacred art remove figures from time, turning human scenes into eternal images. The cocoon can also read as a womb-like shelter, or as a stage-lighting device that isolates the act. A darker interpretation sees it as containment: beauty that can bless, but also trap.

In all readings, the aureole does the same essential work. It completes the union by building a world that belongs to them alone.

#4 Yin and Yang

One of the most accepted core ideas behind The Kiss is a union of opposites. Klimt constructs the lovers as contrasting principles, then locks them into a single form.

The man is built from rectangles, dark blocks, and an upright structure. He initiates, leans forward, encloses. The woman is built from circles, flowers, and organic repetition. She receives, yields, dissolves into bloom. Their bodies speak two visual languages: geometry and nature.

Klimt’s key achievement is that the opposites do not cancel each other. He does not blend them into sameness. The masculine remains masculine; the feminine remains feminine. Yet the pair becomes whole. This is why a Yin-and-Yang reading is so natural: difference becomes the mechanism of completion.

There is also tension in the design. He stands and encloses; she kneels and yields. The union can be read as harmony, but also as the cost of harmony: surrender beneath force. Klimt allows both readings to coexist, which is why the image remains emotionally alive rather than decorative.

#5 The Meadow

The meadow looks safe until you notice where it ends. Klimt places the couple on a small patch of flowers that stops abruptly at an abyss. This single decision turns romance into something more human: love experienced beside the knowledge that it cannot last.

The meadow reads as a sanctuary. Flowers imply fertility, softness, tenderness, life at its gentlest. It is where love can grow. But the edge introduces danger without depicting it. Beyond the flowers is not a landscape. It is absence: the world erased.

The woman’s toes curl over the border, gripping the flowers as if the body knows the risk before the mind admits it. This gesture suggests that their happiness is fragile and precarious. The bliss is vivid, but never guaranteed.

Symbolically, the meadow becomes ‘now,’ and the abyss becomes ‘after.’ Klimt compresses human existence into inches: a strip of life, and the emptiness waiting beyond it. The kiss is not placed in comfort. It is placed at the edge of consequence.

#6 The Kiss

The kiss is the God of the composition. Everything inside the canvas flows toward it: posture, diagonals, hands, and the bending gold. Remove the kiss, and the image loses its center of gravity.

And yet the greatest surprise is that it is not a kiss on the lips. The man kisses the woman’s cheek, or the corner of her mouth, and the moment can even be read as not fully reached yet. Klimt creates intimacy, then denies completion.

This choice produces the painting’s perpetual tension. A kiss on the lips is closure. This kiss is suspension. The act never fully ‘finishes,’ so the scene never becomes the past. Klimt freezes love at the exact second where longing is highest, where meaning is still limitless. The painting stays in the present tense, century after century.

The non-lips kiss also transcends simple erotic satisfaction. Desire is present, even overwhelming, but it is not reduced to bodily consummation. The gesture becomes ceremonial, almost sacred: union as rite rather than appetite.

Finally, the ambiguity forces the moral question. Is this tenderness, blessing, possession, surrender, or all at once? Klimt refuses to prove innocence or dominance. He keeps the kiss slightly unresolved, and therefore endlessly alive.

#7 The Distorted Anatomy

In The Kiss, anatomy is distorted on purpose, and the distortion becomes the illusion’s engine. The scene asks us to accept an impossibility, and we do.

The man is standing; the woman is kneeling; yet their faces meet with intimate precision. Taken literally, the pose does not balance unless he bends sharply, she is unusually tall, or the bodies are not consistent. Klimt chooses inconsistency, then disguises it inside beauty.

Both necks behave like hinges. His neck pushes forward and down; hers tilts back and up. The angles approach a flat, near‑right‑angle bend that would look strained in real life. Yet in the painting, it feels natural, even necessary. Not anatomy, but choreography.

The illusion works because Klimt hides the body under ornament. We cannot measure what we cannot see. He redirects attention to expressive anchors, face, hands, patterns, the kiss. And, most importantly, the distortion serves emotional truth. The bodies bend exactly as needed for the moment to become total.

Here, love is allowed to defy physics without breaking belief. The posture is impossible, but the union feels inevitable.

#8 The Illusion

Klimt’s illusion is not a trick. It is a declaration: when connection becomes absolute, ordinary space and proportion lose authority.

He replaces physical continuity with patterned continuity. Ornament becomes anatomy. The figures dissolve into design so completely that our attention shifts from ‘Is this possible?’ to ‘This is what it feels like.’

In this sense, the illusion does not hide distortion. It transforms distortion into emotional reality. The painting does not claim the body behaves this way. It claims that love, at its most intense, can feel like a force that reshapes the body.

This is why the scene never feels wrong. The illusion is the painting’s ethics: intimacy becomes the standard by which reality is measured.

#9 The Gold

If the kiss is the God of the composition, gold is the religion. It is the substance on which the story is built. In The Kiss, gold is not a color. It is a world.

Klimt’s gold sanctifies human love. The surface recalls icon traditions in which gold is used to mark holiness and timelessness. Here, that visual language is applied to erotic union. Love is treated as worthy of worship.

Gold also suggests wealth, but Klimt redirects the idea. Their true riches are not social or material. Their wealth is love itself: connection, being chosen, being held. The couple becomes royal not by possession of gold, but by being wrapped in it as a metaphor for what is rare.

Yet gold carries a shadow. It can represent obsession, captivity, and the temptation to possess. The gold mantle may bless, but it also encloses. Beauty can become a gilded cage.

Finally, gold isolates the lovers from the real world. It erases landscape, time, and society. The couple exists in a timeless space where love becomes spiritual transcendence. The price of that transcendence is separation from ordinary life: they rise into eternity, and the world disappears.

#10 The Space

Space in The Kiss is not a background. It is an absence. It is ‘the nothing’ that makes this universe possible.

Klimt removes the ordinary environment. No horizon, no weather, no social world, no narrative background. In its place, he gives a gold void that behaves like silence. This emptiness is active. It deletes all distractions until only the union remains.

Because normal space is absent, normal time is absent too. The lovers exist nowhere, and therefore always. Space becomes eternity.

But the same emptiness also suggests isolation. The couple is blessed with total intimacy and also sealed away from life’s continuity. Their universe is complete, yet contains only two.

This is the final logic of the painting. When love becomes absolute, it does not need a world. It becomes the world.

Closing

Here we are again, standing at the edge of that flowered ledge.

The kiss still does not finish. The gold still does not open into a world. And the silence around them still feels larger than the painting itself. Klimt gives us a moment so perfect it becomes untouchable, then traps it there forever.

Maybe that is the secret. Not that love lasts, but that for one breath, it becomes absolute.