Table of Contents

The Fortune Teller — Caravaggio (c. 1595)

Beautiful Theft

Belief rarely announces itself as danger. It arrives softly, dressed as curiosity, as hope, as the promise that something hidden might finally be revealed. We give our attention willingly when we think meaning is about to be offered. Loss does not force its way in. It enters with conversation, with charm, with a hand held just a moment longer than necessary.

This painting understands that truth. It does not accuse. It watches.

A young man extends his hand without hesitation. His posture is open, his expression calm, almost pleased. The Fortune Teller leans toward him, her touch light and practiced. She meets his eyes, speaks gently, and keeps his focus where she needs it to be. Her other hand moves with quiet precision.

Nothing in the exchange feels rushed or hostile. The moment unfolds politely, almost tenderly. Trust passes in one direction. Something else moves away unnoticed.

Painted around 1595, The Fortune Teller, by Caravaggio depicts a street encounter between a well-dressed young man and a fortune teller. While she reads his palm, she discreetly removes a ring from his finger. One of the artist’s earliest genre paintings, the work is known for its realism, psychological insight, and restrained portrayal of deception without overt moral judgment.

Key Facts

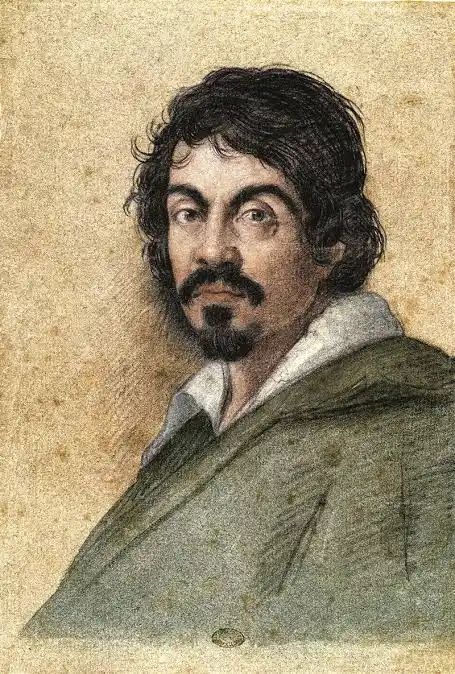

Artist: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Title: The Fortune Teller

Date: c. 1595–1598

Medium: Oil on canvas

Style: Early Baroque

Dimensions: approx. 99 × 131 cm

Current Location: Musée du Louvre, Paris

Versions:

- The Rome Version c. 1594, Housed in the Musei Capitolini, Rome

- The Louvre Version c. 1595–1598, Housed in the Louvre, Paris

Essential Information

About the Artist

Caravaggio arrived in Rome in the early 1590s, at the beginning of his independent career. During this period, he produced small-scale genre paintings intended for private collectors rather than churches or public institutions. These works allowed him to demonstrate his skill while working outside the constraints of academic convention.

Instead of idealized figures or classical subjects, Caravaggio painted from life. His models were drawn from the streets and everyday surroundings of Rome. This approach gave his early paintings an immediacy that distinguished them from the refined artificiality common in late sixteenth-century art. The Fortune Teller belongs to this formative phase, before his turn toward large religious commissions.

Style and Technique

In The Fortune Teller, Caravaggio employs a controlled and even light, without the extreme contrasts that would later characterize his mature work. The figures are clearly modeled, with careful attention to flesh tones, fabric, and gesture. Shadows shape form gently rather than dramatically.

The background is neutral and largely undefined. This decision pushes the figures forward and concentrates attention on their interaction. Brushwork is precise but unobtrusive, supporting clarity rather than spectacle.

Subject Matter

The painting depicts a well-dressed young man consulting a fortune teller, a figure commonly associated in early modern Europe with palm reading and itinerant trades. She holds his hand as she speaks, appearing to read his future. At the same time, she discreetly removes a ring from his finger.

Scenes of fortune telling were familiar in late sixteenth-century Italian art. They often carried associations with deception and naïveté, but they also reflected ordinary urban encounters. Caravaggio presents the subject without exaggeration. The act of theft is visible to the viewer but unnoticed within the scene itself.

Composition

The composition is tightly framed, bringing the figures close to the picture plane. Their bodies form a compact grouping, connected through touch and eye contact. The diagonal created by their arms leads the viewer’s attention directly to the exchange of hands.

No secondary action distracts from the central interaction. The absence of a detailed setting reinforces intimacy.

History and Culture

In Rome during the late sixteenth century, fortune tellers were a familiar presence in public spaces. Their activities existed on the margins of legality and respectability, tolerated but often viewed with suspicion. Paintings depicting such encounters were popular among collectors who enjoyed scenes combining everyday life with subtle moral tension.

While earlier artists often emphasized disorder or overt trickery, Caravaggio’s approach is notably restrained. Rather than staging a dramatic exposure, he captures the moment before awareness arrives.

Commentaries and Discussion

Common Readings and Scholarly Perspectives

Art historians have long read The Fortune Teller as a meditation on deception and vulnerability. The viewer is placed in a position of quiet advantage, aware of the theft while the young man remains unaware.

Some interpretations frame the painting as a gentle moral scene, while others emphasize Caravaggio’s interest in psychology. The exchange unfolds through attention and proximity rather than force, leaving judgment suspended.

The Story Within the Scene

Unlike many depictions of theft, this scene carries no urgency. The Fortune Teller does not rush, and the young man does not resist. The interaction feels ritualized, almost courteous.

The theft is small and precise. One ring. One movement. The moment concludes before it becomes a story of wrongdoing.

Editorial Commentary

Caravaggio does not appear interested in teaching a moral lesson about wrongdoing. He presents a tale and steps aside. There is no outrage here, no condemnation. Even the act of pickpocketing feels strangely light. We do not carry anger toward the woman, and it is easy to imagine that the young man, once aware, might not either.

What emerges instead is a portrait of a rare profession. Fortune telling is shown as a careful balance of beauty, hope, mystery, and unspoken rules. The woman’s skill is persuasion. She steals only one thing, and only in one way. Rings, taken quietly, from those who can afford to lose them. Hearts first, objects second.

In this light, the painting becomes less about loss than about exchange. Attention is given. Confidence is borrowed. Something small is taken in return. Caravaggio allows the moment to remain human, unresolved, and quietly generous.

More About Artist

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) was an Italian painter who single-handedly revolutionized painting and became a pivotal figure of the Baroque art movement. Living a tumultuous and often violent life, he created a body of work that was both intensely realistic and profoundly dramatic. His radical approach broke away from the idealized forms of the Renaissance and Mannerism, influencing a generation of artists known as the Caravaggisti.

Artistic Innovations

Caravaggio’s genius lies in his revolutionary use of a technique now known as tenebrism. This is an extreme form of chiaroscuro that uses a dramatic, single light source to create stark contrasts between light and dark, plunging the background into deep shadow while illuminating the figures in a theatrical spotlight. This technique heightens the emotional intensity of his scenes.

He also shocked his contemporaries with his radical naturalism. Unlike artists who used idealized models, Caravaggio often painted directly from life, using real people—including beggars, laborers, and prostitutes—as models for his saints and biblical figures. This brought a new, raw, and often shocking level of humanity to religious subjects. His paintings feel immediate and tangible, as if the sacred events are unfolding in a contemporary, ordinary setting.

Notable Works

- The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600): This masterpiece, housed in the Contarelli Chapel in Rome, is a perfect example of his style. A single ray of light from an unseen source illuminates the tax collectors in a dark room as Christ, on the right, calls Matthew to follow him. The scene feels less like a historical event and more like a pivotal, everyday moment.

- Basket of Fruit (c. 1599): A truly groundbreaking painting, this is one of the earliest examples of a stand-alone still life in Italian art. Rather than depicting perfect, idealized fruit, Caravaggio rendered the basket’s contents with unflinching realism, including wormholes in an apple and a shriveled leaf. This work is often interpreted as a “memento mori,” a reminder of the transience of life and the inevitability of decay.

- Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1599): This intensely violent and psychological painting depicts the biblical heroine Judith in the act of beheading the Assyrian general. The scene is full of drama and emotion, with Judith’s face conveying a mixture of determination and revulsion.

- The Supper at Emmaus (1601): This work captures the moment the disciples recognize the resurrected Christ. The gestures are explosive, with one disciple’s arms outstretched in shock. The illusion of a meal on the table, with a basket of fruit seemingly about to topple off, brings the divine event into the viewer’s immediate space.

- The Entombment of Christ (1602–1603): Considered one of his greatest masterpieces, this painting focuses on the raw grief of those lowering Christ’s body into the tomb. The light, the weight of the bodies, and the powerful expressions of sorrow create a moving and unforgettable devotional image.