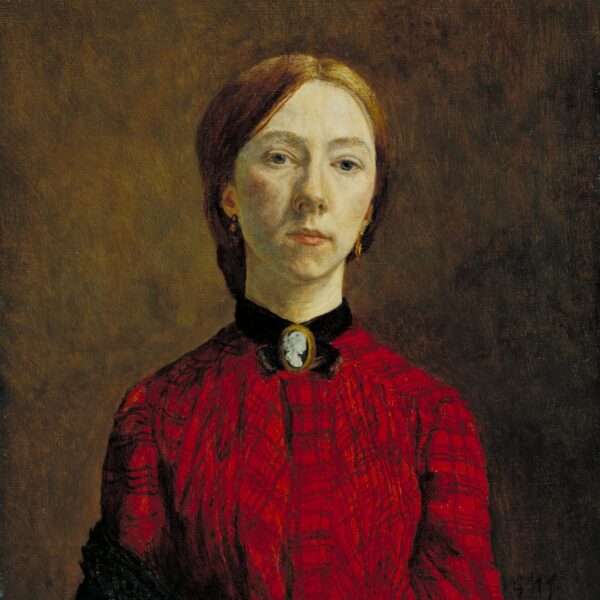

A Beautiful Soul

A woman is seated near a wall.

A room containing almost nothing, yet somehow complete.

She did not chase spectacle. She did not seduce with drama or dazzle with technical display. Her gift was rarer and more difficult. She knew how to remain with a small visual fact until it became meaningful.

Some paintings announce themselves, insist, and perform in bold, in every possible way, to impress.

Our woman, Gwen John, painted almost nothing. Yet we are forced to admire and remember what she created, as if small spells were placed inside ordinary portraits.

Her surfaces are quiet, but never empty. Soft greys, pale greens, powdery creams, colors that seem to breathe rather than shine. The brushwork is restrained. The compositions feel settled, as if they have arrived at the only arrangement that could ever have been thinkable.

We sense care.

We sense peace.

We sense moral weight.

We sense beauty.

We sense trust.

A shoulder turning.

A hand resting.

Light sliding along a wall.

These are not modest subjects treated modestly.

They are modest subjects treated seriously.

The beauty in her work is not about what she felt.

It is about what we feel.

A True Ascetic

Gwen John did not think of herself as practicing asceticism, nor did she label her life as a discipline. There was no sacrifice, training, or framing of virtue; Gwen simply required little. This was not the endurance of someone testing their resolve, but the natural state of a person for whom abundance was never a meaningful category. To her, food existed to keep the body moving, clothing to cover it, and rooms to contain it.

Choosing “less” did not stem from a belief that suffering was noble, nor did Gwen deny herself out of principle or rehearse restraint as a moral act. Excess simply failed to register. Mornings did not begin with a decision to renounce comfort; they began with no particular sense that anything was missing. This marks the difference between an ascetic by conviction and an ascetic by nature. A true ascetic does not experience renunciation as a loss. There is no internal debate, moral tension, or reward for endurance; only a narrow channel of need, accepted without commentary.

Gwen did not consider what such a life might demand from her body. This was not due to self-disregard or a belief that the soul should dominate the flesh, but because the physical self occupied a secondary plane of attention. Focus lived elsewhere: on seeing, on placement, and on the quiet logic of space. The body was merely the vehicle, while the work was the destination.

Even now, one suspects that if Gwen were told what this way of living would eventually cost her, the warning might not fully translate. This would not be a matter of stubbornness, but of distance. The idea that a life so restrained and modest could carry fatal consequences would not easily enter her inner language. To Gwen, nothing extreme was happening. She was not starving; she was living.

The Death

In September 1939, Gwen John was living alone in Dieppe, France.

She was found collapsed on a country road outside the town and taken to the hospital. She died shortly afterward, at the age of sixty-three.

The recorded cause of death was starvation, compounded by weakness and exhaustion.

There is no evidence that she intended to starve herself.

There is no evidence of suicide.

There is no record of a dramatic final act, note, or declaration.

Accounts indicate that she had been living in increasingly poor physical condition, with limited food intake and declining strength.

Her death appears to have resulted from prolonged undernourishment rather than sudden deprivation.

She was buried in Dieppe.

Public attention to her work increased gradually after her death, through exhibitions, critical writing, and institutional acquisitions.

No major recognition occurred during her lifetime.