Table of Contents

Divided Opinions

Van Gogh painted many forgettable people. This group refuses to be forgotten. The Potato Eaters has spent more than a century being argued about.

Some call it clumsy.

Some call it ugly.

Some call it one of Van Gogh’s first serious breakthroughs.

Van Gogh himself considered it important. He believed the heavy faces, thick hands, and coarse features were not mistakes, but choices. He wanted peasants who looked as though they had earned their meal with the same hands that reached into the dish.

To many viewers, that intention never quite lands.

The figures feel swollen.

The space feels cramped.

The faces look carved rather than alive.

For some, ugliness here equals honesty.

This painting sits at an uncomfortable crossroads between ambition and control, empathy and execution, realism and distortion.

Whether it is a failure or a breakthrough depends largely on how much clumsiness one is willing to forgive. That unresolved tension is why The Potato Eaters refuses to go away.

Quick Facts

Artwork Title: The Potato Eaters

Artist: Vincent van Gogh

Year: 1885

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 82 × 114 cm

Current Location: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Collection Type: Museum collection

Market Context & Provenance

Early Market Rejection

The Potato Eaters painting did not begin its life as a desirable object. Early dealers showed little interest. Collectors largely ignored it. Even within Van Gogh’s own circle, the painting failed to generate enthusiasm. It was too dark, too rough, too far removed from prevailing taste.

Van Gogh’s Personal Investment

Van Gogh repeatedly described The Potato Eaters as a serious work. In letters, he defended its clumsy appearance, insisting that the peasants’ coarse faces and heavy hands were intentional. He believed the painting captured people who had ‘earned’ their food through labor.

From a market perspective, this matters.

It establishes the work not as an abandoned failure, but as a painting the artist actively claimed. That claim becomes part of provenance.

From Rejection to Institutional Anchor

The painting’s entry into museum custody transformed its status.

Once absorbed into the Van Gogh Museum, The Potato Eaters shifted from a problematic early effort to a foundational document. Institutional framing converted controversy into historical importance.

Today, the painting functions less as an object of taste and more as a reference point. It anchors Van Gogh’s early Dutch period in exhibitions, catalogues, and scholarship. That anchoring has direct market consequences.

Collectors and Controversial Paintings

Collectors at the upper end of the market do not chase comfort. They chase moments where direction becomes visible.

The Potato Eaters shows Van Gogh before style crystallized, before color exploded, before the familiar Van Gogh existed. It shows intent before mastery.

That is fundamentally different from some other dismissed works, whose market strength comes from belonging to a mature, highly liquid period, such as Madame Roulin and Her Baby, a painting comfortably embedded inside the artist’s highly prized Arles portrait cycle.

This painting’s strength comes from being a turning point.

It is not valuable because it is pretty. It is valuable because it documents a transformation. And in blue-chip collecting, transformation carries more weight than surface beauty.

Aesthetic Breakdown

The painting presents a compressed interior scene lit by a single overhead lamp. Five figures gather around a small table, their faces and hands emerging from a dense brown-green palette. Skin tones lean heavily toward gray and olive, giving the figures a weathered, earthen appearance. Light does not dissolve gently across forms but appears to sit on top of them, creating a dry, chalky surface. The overall effect is somber, heavy, and visually resistant, producing an image many viewers experience as deliberately rough and emotionally dense rather than conventionally appealing.

Structural Problems

From a technical standpoint, the painting exhibits unstable anatomy and compressed spatial organization. Heads appear slightly enlarged in relation to bodies, while hands are disproportionately broad and rigid. Facial features are simplified and sometimes misaligned. Eyes lack consistent placement. Perspective within the room is shallow, offering little sense of recession or depth. Modeling relies more on contour and local color than on gradual tonal transitions, resulting in figures that feel constructed in pieces rather than built as integrated volumes.

At the time, some critics openly mocked the bulbous, distorted faces. One joked that a figure appeared to have only half a nose, an observation that has circulated in commentary on the painting ever since

What People Have Said

From the moment The Potato Eaters appeared, it divided opinion. Not quietly. Not gently. It arrived as a painting that demanded justification. Some saw ambition collapsing under its own weight. Others saw a radical form of honesty. Over time, both camps have continued to grow.

The Detractors

Unfinished and Incorrect

Anton van Rappard

Several of Van Gogh’s contemporaries regarded the painting as technically unsuccessful. Fellow artist Anton van Rappard, who had previously been supportive of Vincent, expressed strong dissatisfaction after seeing the work, pointing out problems in proportion, anatomy, and overall construction. Van Gogh acknowledged this criticism in letters, though he firmly disagreed with its conclusion.

Clumsy Figures

Early Critics

Early viewers frequently described the peasants as awkward, stiff, and poorly drawn. Heads appear oversized. Hands look exaggerated. Faces feel mask-like. For critics trained in academic draftsmanship, these qualities signaled incompetence rather than intention.

Too Dark, Too Brown

Contemporary Reviewers

The palette also attracted negative attention. Many felt the painting was suffocatingly dark and muddy, lacking the clarity and tonal separation expected of a large multi-figure composition. Compared to contemporary realist painting, The Potato Eaters was seen as visually crude.

Social Realism Without Elegance

Academic Commentary

Some critics objected to what they perceived as a lack of refinement. The peasants were not idealized. Their faces were not softened. Their environment was not beautified. For audiences accustomed to polished genre scenes, this bluntness read as failure rather than a statement.

In short, detractors largely framed the painting as an overambitious early effort that exposed Van Gogh’s limited training and weak technical foundation.

The Defenders

Deliberately Coarse

Van Gogh

Van Gogh repeatedly defended The Potato Eaters in letters to his brother Theo. He argued that the roughness was deliberate. The peasants, he wrote, had dug the potatoes from the earth with the very hands now reaching into the dish. Their coarse features were meant to reflect lives shaped by labor, not studio polish.

For Van Gogh, smoothness would have been dishonest.

Moral Realism

Later Historians

Later historians began to describe the painting as an early example of moral realism rather than a technical failure. The goal was not beauty, but ethical weight. The painting attempts to show people who live close to the soil, eating the product of their own work, without romantic gloss.

A Serious First Statement

Modern Scholarship

Many scholars now view The Potato Eaters as Van Gogh’s first consciously “serious” painting. It marks his attempt to enter the tradition of socially engaged realism associated with artists such as Jean-François Millet, whom Van Gogh deeply admired.

Clumsiness as Expression

Museum Catalogues

Defenders argue that the awkward anatomy contributes to the emotional tone. The heaviness of the figures reinforces fatigue. The compressed space intensifies claustrophobia. The ugliness becomes part of the meaning rather than a flaw to be corrected.

Foundational, Not Decorative

Modern Scholarship

Within modern scholarship, the painting is often discussed less as a visual success or failure and more as a foundational document. It shows Van Gogh deciding what kind of painter he wanted to become.

What makes The Potato Eaters endure is not consensus. It is resistance to consensus. Some still see a badly painted scene. Others see a raw ethical position. Both readings continue to coexist. And that unresolved tension may be the painting’s most stable achievement.

A CENTURY OF DEBATE

A Supper Without End

This group has been sitting at the table for more than a hundred years. They are still waiting for the debate to settle so they can finish their dinner. ‘The single plate of potatoes.’

While Van Gogh wanted to paint people who had earned their meal, some viewers see honesty. Some see awkwardness.

Both readings have existed from the beginning.

The Potato Eaters does not offer ease.

It does not offer decoration.

It offers a moment where intention and execution collide. What survives is not agreement. What survives is the argument.

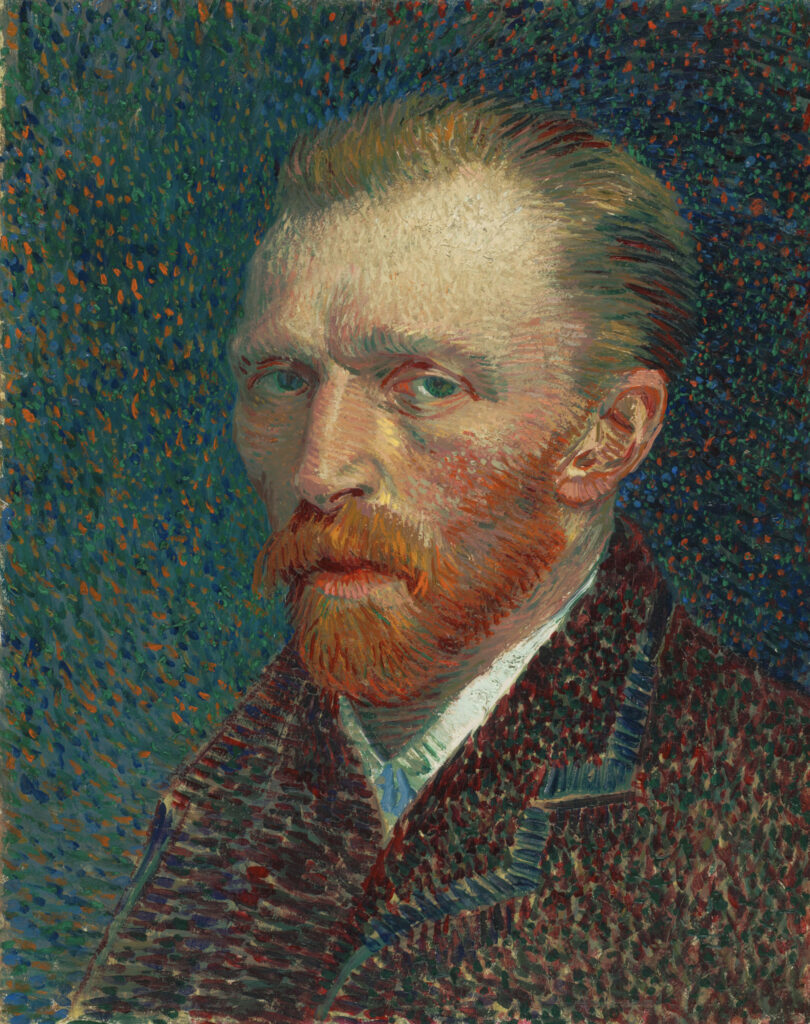

About Artist

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter whose brief career produced more than 800 oil paintings and over 1,000 works on paper. Working largely outside academic systems, he developed a highly personal language of color, impasto, and line that influenced modern art profoundly. During his lifetime, he sold almost nothing. Today, his work anchors museum collections worldwide and occupies a central position in the global art market.